|

The Man Who Fell To Earth

1976

138 minutes | Colour | 2.35:1

Director : Nicolas Roeg

Producers : Michael Deeley and Barry Spikings

Screenplay : Paul Mayersburg, from the novel by Walter Tevis

Cinematography : Anthony Richmond

Executive Producer : Si Litvinoff

Musical director : John Phillips

Editor : Graeme Clifford

Cast

David Bowie : Thomas Jerome Newton

Rip Torn

: Nathan Bryce

Candy Clark : Mary-Lou

Buck Henry : Oliver Farnsworth

Bernie Casey : Peters

Jackson D. Kane : Professor Canutti

Rick Riccardo : Trevor

Tony Mascia : Arthur

Captain James Lovell : himself

Filming locations

New York and Los Angeles and several areas of New Mexico: Albuquerque, Artesia, Fenton Lake State Park (455 Fenton Lake Road, Jemez Springs), Madrid, Roswell, White Sands Missile Range, near Alamogordo, White Sands National Monument, near Alamogordo

Distribution

Great Britain: British Lion

USA: Cinema

5

Cinema 5 cut the picture

when it was first distributed in America. Prints ran at 117, 120

or 125 minutes, according to different sources. In 1980 a new regime

at Cinema 5 restored the picture to its original length.

Casting

As the main character in Walter Tevis’s book The Man Who Fell To Earth, Thomas Jerome Newton, was unusually tall, English director Nicolas Roeg’s first casting choice was the six-foot-nine inch-tall writer Michael Crichton, despite the fact he had no acting experience. He was unavailable so Roeg and executive producer Si Litvinoff turned to CMA casting agent Maggie Abbott.

Si Litvinoff (2002): She was David (Bowie)’s agent at the time. She represented all their ‘boutique’ people, who were not necessarily known as actors or movie stars.

She suggested CMA artist Mick Jagger, whom Roeg had directed in Performance.

Maggie Abbott (2005): I tried to talk him into Mick but Nic knew him so well and said he wasn’t what he had in mind. He wanted someone who looked frail – as if he had no bones in his body – and I immediately cried out, ‘David Bowie!’ He had just the charisma the character required. It had nothing to do with acting experience.”

She had seen Cracked Actor and, after their meeting, obtained a copy to show to Litvinoff and Roeg.

Bowie (1976): Nic watched it and I guess it was my attachment to Ziggy, the alter ego that captured his interest and imagination. And my looks helped, too. Roeg wanted a definite, pointedly stark face – which I had been endowed with.

They immediately recognised that, like Newton, Bowie was a ‘foreign body’, uncomfortable in a new climate.

Bowie (1993): I think one of the things that Nic identified with me is that I was definitely living in two separate worlds at the same time. My state of mind was quite fractured and fragmented but I didn’t really have much emotive force going for me so it was quite easy for me not to relate too well with those around me.

Roeg and Litvinoff were convinced – now they had to convince Bowie. Maggie Abbott took Paul Mayersberg’s script round to him and was shocked at his ‘ghastly’ appearance. Bowie’s initial response to the script was cautious but he agreed to meet them at his house on West 20th Street.

Ava Cherry (2010): He’d spoken of doing movies, but I don't think anyone offered him a serious script before Nic Roeg. He wanted to be a movie star because he admired musicians who had acted, the Frank Sinatras. It was a natural progression for him. Mick [Jagger] had done some films. They were friends – he wanted to do films, too.

Paul Mayersberg (2012): Bowie took some persuading. As a joke, I put in a scene showing Newton unable to sing.

Bowie would be in a recording studio till 10pm so Roeg arrived at 9.30, followed later by Litvinoff.

Si Litvinoff (2002): I went downtown – and I recall it was snowing – to David's rented house. A lovely black girl with short-cropped orange hair and a Clockwork Orange sweater, of all things, opened the door.

Litvinoff had produced Kubrick’s film and so took this as a good omen. As Roeg chatted to the “strangers coming and going” they waited. And waited.

Bowie (1993): I was out and when I remembered the appointment I was already an hour late, so I thought, "Oh, no, I missed him, he won't be there now," and just forgot about it. When I finally got home, there was Nic waiting for me, sitting in my kitchen very patiently. Eight hours late and the man waited for me! That's persistence, you know, isn't it?

Nic Roeg (1993): At about five o’clock he arrived. We spoke for about five minutes. He said “I’m tired”. I said, “I can understand that – so am I” and he said, “Don’t worry, I’m going to do it.” And he showed me to the door. I was obviously looking a bit stunned – [having been there] from 9.30 ‘til 5.30 in the morning!” [He said] “I tell you, don’t worry. Let me know when you want me. I’ll be there.

Bowie (1993): What I didn’t tell him that day when he turned up was that I hadn’t actually read The Man Who Fell To Earth. And it was a combination of having seen Walkabout and actually meeting Nic in person that convinced me that this was something I should definitely get involved with… I tried to kill the conversation as quickly as possible because I didn’t want him to suss that I hadn’t read it. So he was throwing bits of the film at me and I was, “Yes, quite, quite… oh absolutely… oh yes, I can see that.” But it was probably the best decision based on absolutely nothing – other than a man’s previous work – that I’ve probably ever made.

Watching Bowie

in Alan Yentob's 1975 BBC documentary Cracked

Actor, Nicolas Roeg realised he was looking at someone who, without any

real experience in film, was perfect for the lead role in Roeg's

upcoming feature, The Man Who Fell To Earth.

This character, Thomas

Jerome Newton, possessed many of the qualities Bowie was displaying

in Cracked Actor — cerebral, edgy, enigmatic — a fragile alien

uncomfortable in a new climate. Uncomfortable in his own skin.

At the

time Bowie was taking the gargantuan Diamond Dogs 'Theatour' across

America, which for him, "had always been a mythland."

"Since you’ve been in America,” Yentob asks him, “you seem to have picked up a lot of the idioms and themes of American music, American culture. How’s that happened?”

By way of explanation, Bowie looks in his milk carton and observes, "There's a fly floating around in my milk. It is a foreign body and it's getting a lot of milk! That's

kind of how I felt — a foreign body and I couldn't help

but soak it up."

The analogy was obvious for Roeg: Both Bowie and Newton arrive in a foreign world, each with a particular mission. Newton wants to transport water back to his desert planet Anthea. Bowie wants to continue writing and performing, as he explains to Eyewitness News presenter Wayne Satz, "to

keep me interested, to keep the people who come to see me or buy

my records interested and excited as well."

Satz wrapped up his report saying, "If you didn't understand that, don't feel badly, because I certainly didn't". Newton too finds himself misunderstood in America and is eventually regarded as a threat.

Bowie had been offered many movie roles in the past

year but they were mostly ludicrous exploitation flicks based on his Ziggy/Starman image. But here

was a respected director with a role that very natural

for Bowie. He would just be himself.

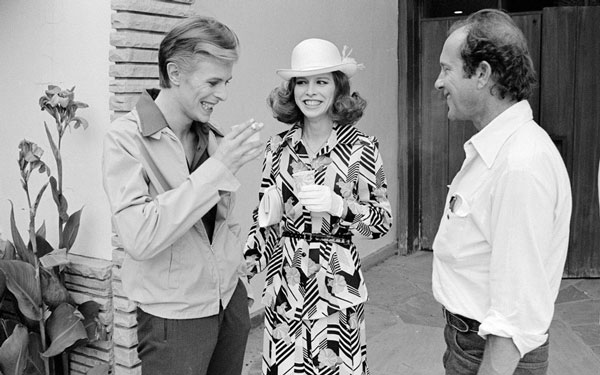

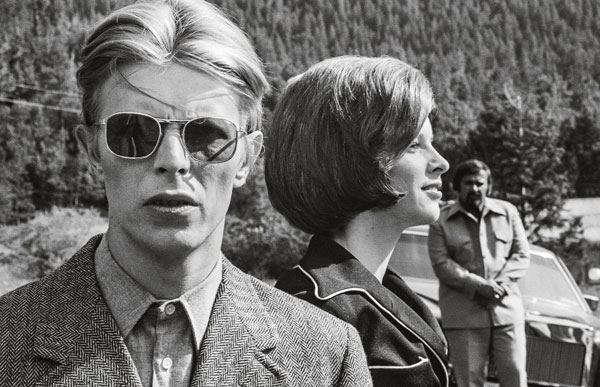

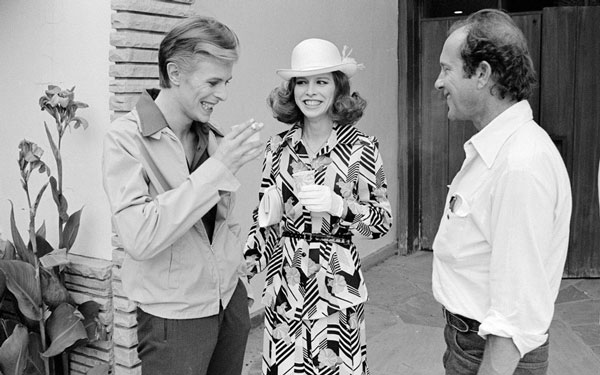

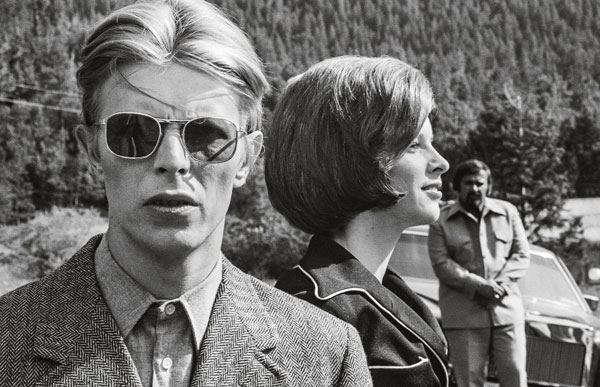

Discussing the script with Nic Roeg • Photo © David James

Photo © Steve Schapiro

According to Roeg, Bowie threw

himself into it, always on time and putting in a performance which

everyone was happy with, even himself. It would be the only film he

would go out of his way to promote (using stills for the covers

of Station To Station and Low).

The remarkable thing about the Bowie film canon is

that every character ends up being degraded or martyred. It is perhaps

a sign that Bowie has always felt like a marked man and has by nature

flaunted this to dare his persecutors.

Production: June–August 1975

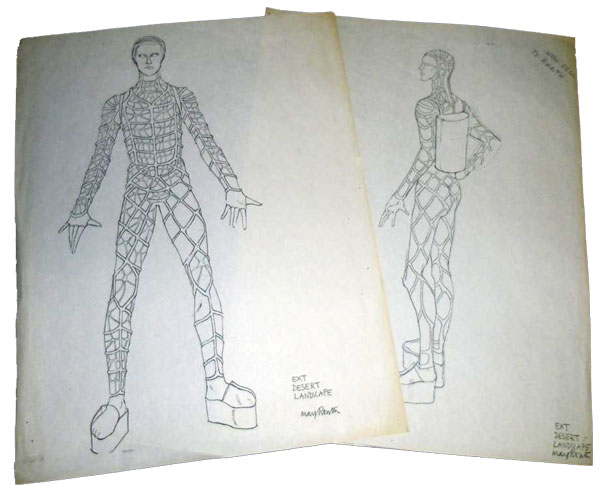

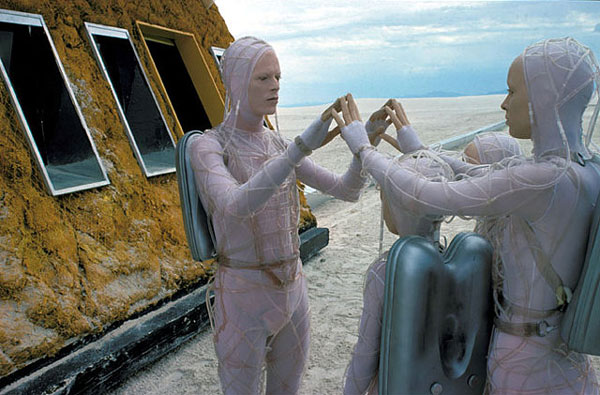

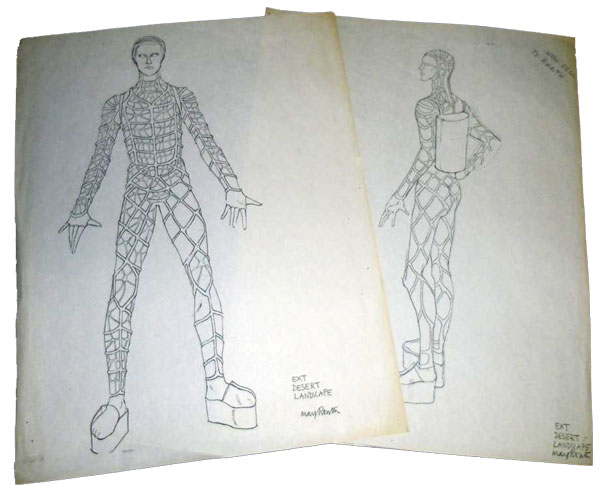

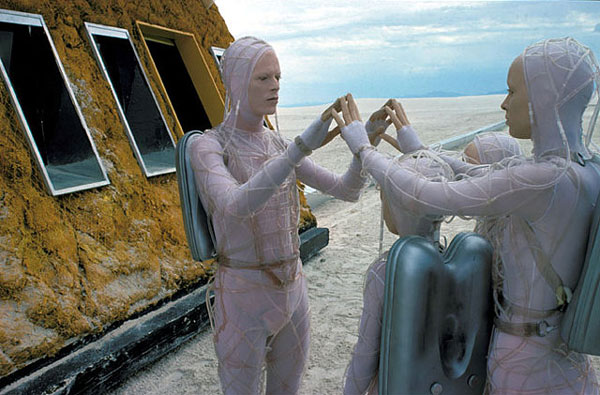

May Routh's wardrobe designs for the Anthean scene

Bowie and MacCormack rode the Amtrak Santa Fe Super Chief train from Los Angeles to Albuquerque, arriving on the set in a limo similar to that seen in Cracked Actor. Roeg cast both the car and Bowie’s driver Tony Mascia as Newton’s chauffeur Arthur.

Bowie, Candy Clark and Tony Mascia • Photos © David James

For the first two weeks the production was based at the Albuquerque Hilton Inn. Bowie’s presence in the town was kept under wraps. Reporters were warned, “Mr Bowie does not wish to be interviewed or photographed.”

During the first two weeks Bowie, Schwab and MacCormack moved to a ranch in the hills above Albuquerque.

Principal photography began in Los Lunas, which Roeg was pleased to discover was Spanish for ‘The Moons’. The first day of shooting covered Newton’s arrival in Haneyville (a fictitious name from the original book), the pawn shop where Newton sells the first of his rings and the river where he toasts his first sale with a cup of murky water.

Newton’s first appearance was shot at an abandoned mine in Madrid, a small town 20 miles east of Santa Fe. Albuquerque locations included the First National Bank, the First Plaza and its water fountain.

David Cammell (brother of Performance director Donald) told The Albuquerque Tribune, “There have been no problems, and everything is going fine. We have found everybody to be most cooperative.”

25 Albuquerque residents were given speaking roles and used as extras in the movie. After two weeks production moved north to Artesia for the scenes in the eight-storey Hotel Artesia, which was abandoned except for the bar on the ground floor.

Brian Eatwell, production designer (2005): It was great because they were only too pleased to co-operate and the room [Newton] lives in was actually a little larger than you establish in the film. Because it was empty, the owner didn’t care too much what we did, so I had a local contractor to come in and knock down several walls to make filming easier.

Scenes set on Newton’s planet Anthea were shot at White Sands Missile Range near Alamogordo. Bryce’s house was a converted park ranger’s house beside Fenton Lake. On the far side of the lake was Newton’s house but the interiors were shot in a brand-new unoccupied adobe house in Santa Fe.

Paul Mayersberg, screenwriter (2012): As a location, New Mexico was heaven sent: there are more sightings of UFOs over its deserts than in the rest of the world. It gave Nic a wonderful palette: you really got the feeling you were on a planet floating in space. We shot near Alamogordo and White Sands, near where they tested the atomic bomb. They still had no entry signs up.

Tony Richmond, cinematographer (2012):

I was Nic's clapperboy for many years. Then he pushed me up to focus-puller, then assistant cameraman, and then I ended up shooting Don't Look Now. So I was very conscious of how he worked, and we were very close. We were on a short schedule for this – movies were different then. We were a lean, light crew, mostly British, and we found going on the road through New Mexico a wonderful experience: Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Fenton Lake, all over.

I can't think of anyone else who could have played Newton. Bowie was so strange, so ethereal, so androgynous. I never saw him using any drugs on set. He had a minder looking after him, as well as a chauffeur, Tony Mascia, who played the same role in the film. He had recently started looking after his son Zowie [now Duncan Jones], who came out to visit.

He was great to work with – a bit weird, but great. He always turned up on time. He went a bit funny for a few days, because he thought someone had put something in his orange juice. He was a very sensitive guy. In one scene, surgery is performed on him. I didn't like the colour of the makeup blood, so I said to the props boy: "Nip down to the butcher and get some pig's blood." Bowie heard that and wouldn't entertain it. But he would entertain human blood. We had a nurse on set, and Nic made her take my blood. Can you imagine doing that nowadays?

[How we made: Paul Mayersberg and Tony Richmond on The Man Who Fell to Earth, Phil Hoad, guardian.co.uk, 25 June 2012]

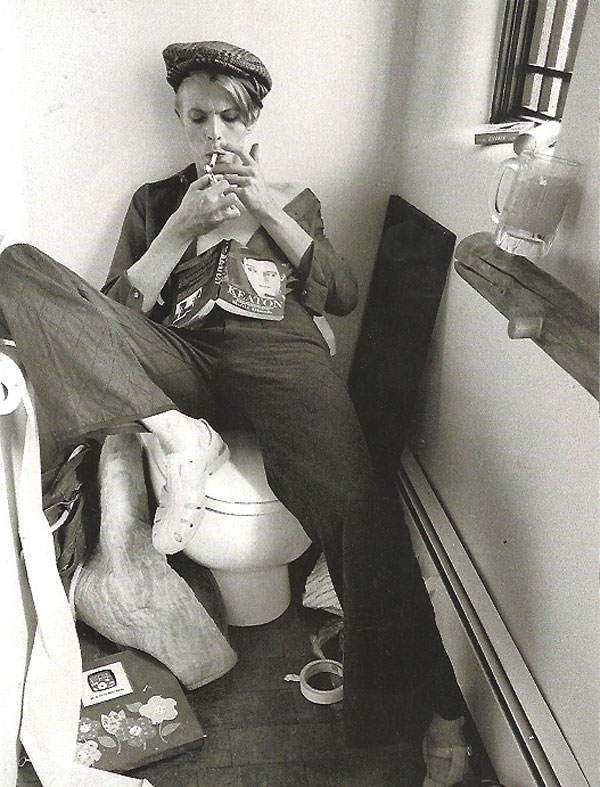

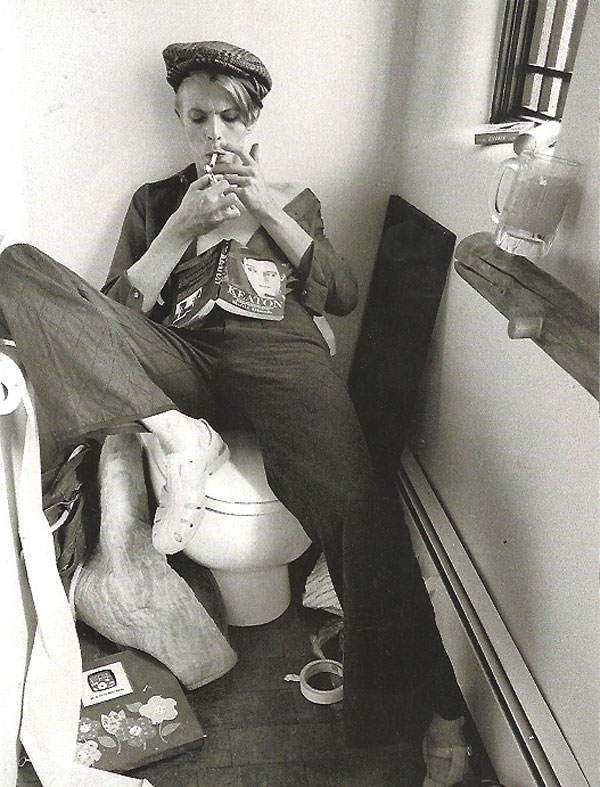

Other projects included writing songs for his next album Station to Station, researching a mooted biopic of Buster Keaton, writing his autobiography The Return of the Thin White Duke and reading.

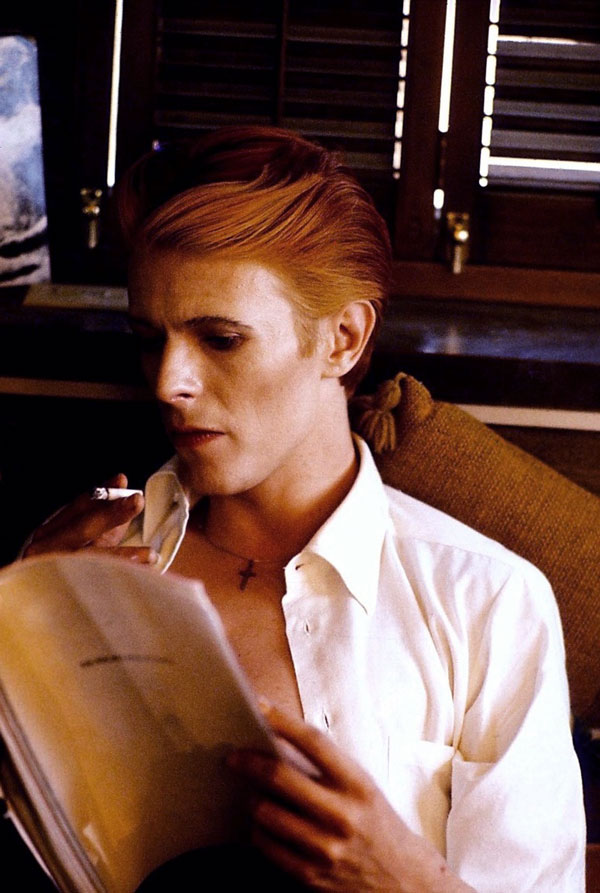

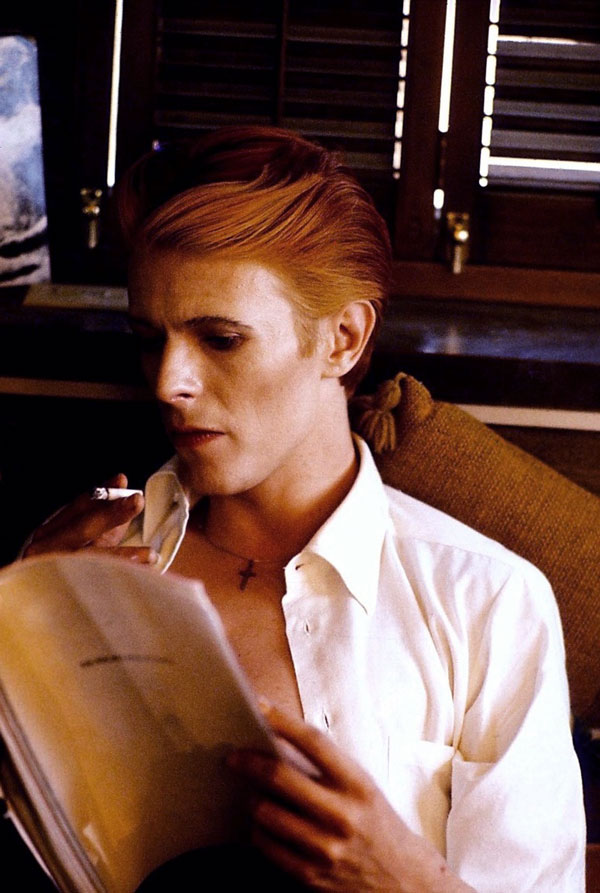

Reading a Buster Keaton biography • Photo © Steve Schapiro

Bowie (1999): I took 400 books down to that film shoot. I was dead scared of leaving them in New York because I was knocking around with some pretty dodgy people and I didn't want any of them nicking my books. Too many dealers, running in and out of my place.

Photographed on set by Steve Schapiro

Used as cover photograph for Rolling Stone magazine February 1976

The lost soundtrack

The original plan was that RCA would contribute to the film and Bowie would provide a soundtrack that included singles that would serve to promote the film.

August 1975

Creem magazine: Are you doing any music for the film?

Bowie: Yeah, all of it. That'll be the next album,

the soundtrack. I'm working on it now, doing some writing. But we

won't record until all the shooting's finished. I expect the film

should be released around March, and we want the album out ahead

of that, so I should say maybe January or February.

November 1975

Following the October recording sessions for Station to Station at Cherokee Studios in Los Angeles, Bowie asked Roeg and Michael Deeley to engage Paul Buckmaster for the soundtrack sessions to be recorded at Cherokee Studios, with Harry Maslin and engineer David Hines.

Paul Buckmaster (2017): They flew me to LA and put me up in the Sunset Marquis for around three months. [David’s place] was a beautiful, large house, with a huge open-plan living room/dining area. He had set-up a [Fender] Rhodes [piano] and a couple of other keyboards. There were no drum machines, sequencers or computers, so everything had to be done in real time. We didn’t have a multitrack [recorder] in his house. We had video tapes and we didn’t go to any screenings. We had the Rhodes, an ARP Odyssey and an ARP Solina, which was an early string synthesiser, and we basically jammed together, trying out ideas, until we were satisfied they would work against [with] the images. (interview by George Cole, Record Collector 2017)

Paul Buckmaster (2007): There were a couple of medium tempo rock intrumental pieces, with simple motifs and riffy kind of grooves, with a line-up of David's rhythm section (Carlos Alomar, George Murray and Dennis Davis) plus J Peter Robinson on Fender Rhodes piano and me on cello and some synth overdubs, using ARP Odyssey and Solina.

There were some more slow and spacey cues with synth, Rhodes and cello; and a couple of wierder atonal cues using synths and percussion. There was a ballad instrumental by David that appears on Low [Subterraneans]. It was performed by David, me and J Peter on various keyboards.

There was also a piece I wrote and performed using some beautifully made mbiras (African thumb pianos) I had purchased earlier that year, plus cello, all done by multiple overdubbing.

And a song David wrote, played and sang, called Wheels, which had a gentle sort of melancholy mood to it. The title referred to the alien train from his character Newton's home world. (interview by David Buckley, Mojo 2007)

Bowie was still under the impression that the music would be used, telling the host of Soul Train, "I'm doing the soundtrack for The Man Who Fell

To Earth with a friend of mine, Paul Buckmaster".

December 1975

Nic Roeg was cutting the film at Shepperton Studios in Surrey, where he spoke with Mike Flood Page from UK music paper Street Life.

[Roeg] has before him a miniature Sony cassette machine and offers an exclusive preview of the Bowie soundtrack just in from LA. It's a simple melodic instrumental based around organ, bass and drums, with atmosphere courtesy of studio wizardry all put together and performed by Bowie himself.

Roeg and executive producer Si Litvinoff thought the recordings were brilliant, but fell short of being a usable soundtrack. Instead John Phillips was assigned the job of putting together a soundtrack in London. Phillips had heard Bowie's score, and later described it as "haunting and beautiful, with chimes, Japanese bells, and what sounded like electronic winds and waves".

Harry Maslin (1985): David was so burned out by the end of Station To Station, he had a hard time doing movie cues. The movie was complete and we had all the videotapes and that was what we were working with. We had about about nine cues down – of the sixty that we needed – and David had a big blowup with Michael Lippman.

Paul Buckmaster (2001): It was just not up to the standard of composing and performance needed for a good movie; secondly, I don't think it fitted well to the picture; and lastly, it wasn't really what Nic Roeg was looking for. I considered the music to be demo-ish and not final, although we were supposed to be making it final. We also didn't have a producer at the time and we were just trying to hammer it out together. All we produced was something substandard and Nic Roeg turned it down on those grounds.

John Phillips (1986): Roeg wanted banjos and folk music and Americana for the film. Roeg said, ‘David really can’t do that kind of thing. We asked him who he thought he would like to do it and you were the first name that popped out of his mouth.’

Si Litvinoff (2002): To make matters worse, (British Lion producer) Deeley tried to outsmart David on the music rights. David turned him down. Thus, the great music Bowie wrote for the picture couldn't be used. The [John Phillips] soundtrack is a meaningless last-minute replacement for what was superb.

Bowie (1993): I presumed – I don’t know why but probably because I was arrogant enough to think it so therefore I acted upon it – that I had been asked to write the music for this film. And I spent two or three months putting bits and pieces of material together. I had no idea that nobody had asked me to write the music for this film; that in fact, it had been an idea that was bandied about.

Bowie (2002): I got angry about it, with no real rational reason. I thought I should be contracted by the film company to do the soundtrack, not just make a presentation of ideas. A stupid juvenile reason but I kind of walked away from it.

Bowie (1993): I constructed a thing, which never became the soundtrack to the movie, but become the album Low. Some if it went onto Station To Station, another chunk of it went onto Low.

Ricky Gardiner, guitarist on Low: He wasn’t pleased it wasn’t used in the film. He let us hear it and it was excellent, quite unlike anything else he’s done.

Brian Eno (1976): Two of the [Low] pieces are from the soundtrack he made for The Man Who Fell To Earth and he added things and remixed them.

Nic Roeg (1993): Some time later, David sent me the album – he said, ‘This was the music I would have done for The Man Who Fell To Earth.’

The soundtrack remains an enigma. Only a few have heard the tapes, and future of those tapes is uncertain, especially since their owner, Paul Buckmaster, died November 2017.

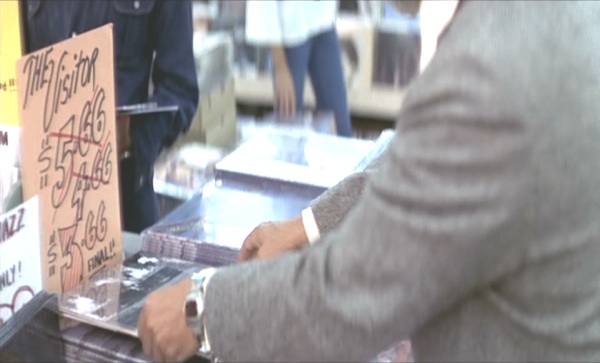

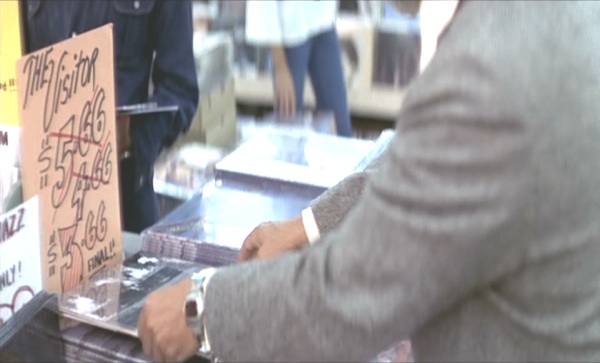

The Visitor

In the film Thomas Jerome Newton records and releases an album called The Visitor in the hope that it will be broadcast on the radio and heard by his wife on his home planet, Anthea.

Nathan Bryce visits a local record store (where he passes a row of Young Americans promotional posters), where he finds a marked down copy of Newton's record, The Visitor.

Taking the record cover as a clue, he tracks down Newton to the restaurant pictured on it – Butterfields in Los Angeles.

Newton: Did you like it?

Bryce: Not much.

Newton: Oh, I didn’t make it for you anyway.

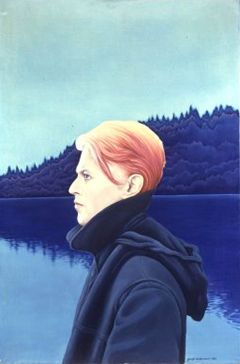

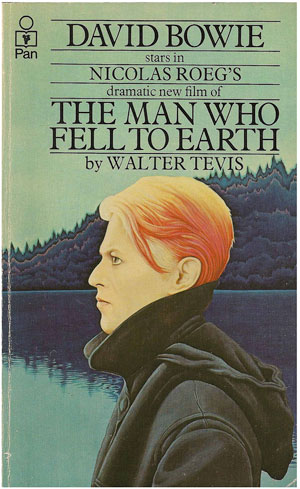

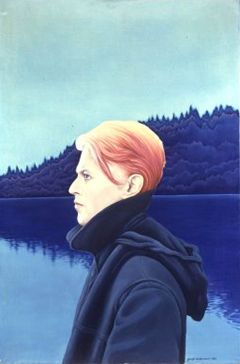

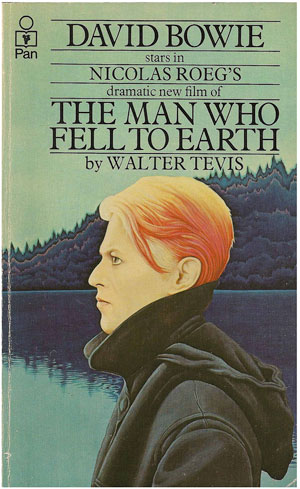

To promote and cash in on the film on its release in March 1976, Pan Books had prepared and distributed a movie tie-in edition of Walter Tevis’ novel with a cover illustration by George Underwood.

The back cover on the first edition read:

‘Music by David Bowie. Album available on RCA.'

When it was apparent this would not be the case, the second printing was amended to:

‘Musical Director John Phillips’

with no mention of an album by Bowie. As a result, the album of Bowie's unreleased soundtrack music became the stuff of legend.

In the discography of their 1981 book, Bowie: The Illustrated Record, Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray listed a bootleg titled David Bowie Is 'The Visitor'. They described it thus:

"Supposedly Bowie's original soundtrack for The Man Who Fell To Earth, it contains an early version of Weeping Wall, plus other instrumentals and some dialogue from the film."

This was a hoax.

Charles Shaar Murray: Roy and I made that one up. It was an old trick of Roy's, designed to let him know whether anybody else was nicking his research rather than doing their own.

In September 1992 Vox magazine reported that Netherlands-based Farnsworth label was to release a limited edition CD soundtrack of The Man Who Fell To Earth. Housed in a steel box, the set would include a copy of the script, a set of 12 production stills, a cinema lobby card and a replica of Newton’s gold wedding band.

The CD would include all of the music from the original soundtrack (this too had never been released), intercut with dialogue from the movie. The main attraction was the inclusion of a “10-minute segment of instrumental ambient music, composed by Bowie, but never used in the final cut.”

This too was a hoax.

Post production

The film was due to open 18 March in England. Meanwhile US distributors Cinema 5 had drastically cut the film down by 20 minutes to two hours for its US premiere in May.

Si Litvinoff (2002): Editing is my favourite stage after development. But in this movie, (British Lion producers) Deeley and Spikings replaced me in London. They had promised Nic that nobody would recut his cut. As my lawyer described it politely, Deeley tried to outsmart Paramount, which pulled out of the deal. The rights to the picture were then sold to an exhibitor, not a studio. And the exhibitor had the picture recut. [409][lukeford.net – Si Litvinoff interview (2002)]

Candy Clark (2005): You really couldn’t make head or tail of the cut version. They hired some people who edited commercials to do it. And this after Nic Roeg and editor Graeme Clifford had spent nine months cutting it. I was due to go on the road for Cinema 5 to promote it, but I bailed out after a day. It was making me sick. [154][Hughes, Rob. ‘Loving the alien’ (Uncut, December 2005)]

Production stills

Cinema release and promotion

Video releases

Si Litvinoff profile

Sources and further reading

Nic Roeg and David Bowie commentary

The Man Who Fell To Earth (DVD Criterion, 1993)

'Watching The Alien' featurette

The Man Who Fell To Earth (DVD Studio Canal, 2002)

Rob Hughes : Loving the alien (Uncut, December 2005)

John Robinson : Run for the shadows (Uncut, July 2010)

Phil Hoad : How we made The Man Who Fell To Earth

(The Guardian, 25 June 2012)

Reports from the set:

Kept under wraps in Albuquerque (The Tribune, 14 June 1975)

Spaced Out in the Desert (Creem, December 1975)

Glitter Rock’s Movie Nut (Baltimore Sun, 20 June 1976)

|