|

Young Americans

released March 7, 1975

RCA RS 1006 (UK) • APL1-0988 (US)

Chart peak UK 2 US 9

Side one

Young Americans* 5:10

Win** 4:44

Fascination** (Bowie-Vandross) 5:43

Right** 4:13

Side two

Somebody Up There Likes Me** 6:30

Across The Universe*** (Lennon-McCartney) 4:30

Can You Hear Me*** 5:04

Fame*** (Bowie-Alomar-Lennon) 4:12

David Bowie vocals, guitar

Dennis Davis drums

Andy Newmark drums

Emir Ksasan bass

Willie Weeks bass

Mike Garson musical director, keyboards

Carlos Alomar rhythm guitar

John Lennon guitar (on Across The Universe and Fame)

Earl Slick guitar

David Sanborn alto saxophone

Ralph McDonald percussion

Pablo Rosario percussion

Larry Washington percussion

Ava Cherry backing vocals

Robin Clark backing vocals

Anthony Hinton backing vocals

Warren Peace backing vocals

Diane Sumler backing vocals

Luther Vandross backing vocals

Jean Fineberg, Jean Millington backing vocals (on Fame)

String arrangements by Tony Visconti

Vocal arrangements by David Bowie and Luther Vandross

Produced by

*Tony Visconti

**Tony Visconti and Harry Maslin

***David Bowie and Harry Maslin

Recorded at Sigma Sound Philadelphia

(Engineer Carl Paruolo; Tape operator Mike Hutchinson)

except Across The Universe and Fame at Electric Lady, New York

(Engineer Eddie Kramer; Tape operator David Whitman)

Mixed at Record Plant, New York

(Engineer Harry Maslin; Tape operators Kevin Herron, David Thoener)

except Young Americans at Sound House, London

Cover design by David Bowie

Photography by Eric Stephen Jacobs

Selected reissues

October 1984 RCA CD

May 1991 Rykodisc/EMI CD

remastered with bonus tracks:

Who Can I Be Now? 4:35

It's Gonna Be Me 6:29

John, I'm Only Dancing (Again) 6:58

April 1997 Rykodisc Au20 CD

September 1999 EMI remastered CD

February 2007 Toshiba EMI mini LP replica CD

2007 EMI CD/DVD

remastered with bonus tracks:

John, I'm Only Dancing (Again) 7:03

Who Can I Be Now? 4:39

It's Gonna Be Me [alternate version, with strings] 6:28

5.1 surround mix DVD: The Dick Cavett Show

(1974)

Dick Cavett interviews David Bowie 16:01

1984 3:07

Young Americans 5:11

Releases of non-album Young Americans sessions

John I'm Only Dancing (Again)

7 and 12-inch single (RCA 1979) and Rare LP (RCA 1983)

After Today (3:50)

Sound + Vision box set (Ryko 1989)

It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City (Springsteen) 3:49

Sound + Vision box set (Ryko 1989)

Best Of 1975/1979 (EMI 1997)

Bowie (1975):

‘Young Americans’ is about a newly wed couple who don’t know if they really like each other. Well, they do, but they don’t know if they do or don’t. It’s a bit of a predicament.

‘Win’ was a “get up off your backside” sort of song really – a mild, precautionary sort of morality song. It was written about an impression left on me by people who don’t work very hard, or do anything much, or think very hard – like don’t blame me ‘cause I’m in the habit of working hard. You know, it’s easy – all you got to do is win.

‘Right’ is putting a positive drone over. People forget what the sound of Man’s instinct is – it’s a drone, a mantra. And people say, “Why are so many things popular that just drone on and on?” But that’s the point really. It reaches a particular vibration, not necessarily a musical level. And that’s what ‘Right’ is…

‘Somebody Up There Likes Me’ is a “Watch out mate, Hitler’s on his way back”... it’s your rock ‘n’ roll sociological bit. [RAM 1975]

Production

August 11–22, 1974

Sigma Sound, Philadelphia

Producer: Tony Visconti

Young Americans

John I'm Only Dancing Again

Never No Turnin' Back

[version 1, later re-recorded as Right]

Somebody Up There Likes Me

Who Can I Be Now

Come Back My Baby [later retitled It's Gonna Be Me]

Take It In, Right [version 1, later re-recorded as Can You Hear Me]

After Today

It's Hard To Be A Saint In The City [backing track]

Funky Music (Is A Part Of Me) [later rewritten as Fascination]

Tony Visconti: I arrive in Philadelphia from London around 8pm. I've just finished a Thin Lizzy album and I am tired! I am rushed to Sigma Sound by limo. I am shown the control room, and can see a large band playing full tilt with Bowie walking around pensively among them. I am immediately intimidated because the band contains three musicians I am in complete awe of – Andy Newmark on drums, Willie Weeks on bass and David Sanborn on sax. These are super session men, and I'm just a Brooklyn kid who did good in England!

Visconti and Willie Weeks • David Sanborn and Carlos Alomar

I ask the engineer Carl Paruolo, "Who is engineering?" I've never seen a console as funky as this – it looks like it was handmade in someone's garage on weekends. He says, "You are!"

He was originally selected to engineer by Bowie, having recorded many Philly hits, but he told me that Bowie wasn't pleased with the sound. Bowie told Carl, "Tony will be handling the recording once he arrives."

David and the band had been recording their rehearsals for three days, and I could hear the problem he had with the sound. In those days, in America, engineers recorded "dry" and "flat", waiting for the mix to add the equalization, reverbs and special effects. But the British often recorded with the special effects right on the session! I was British-trained and David was used to this sound! So I rolled up my sleeves and got right into it. By 2am we'd recorded our first official backing track – Young Americans.

The session guys were great to record with. My fears were quickly dispelled. To contrast the "slickness" of Newmark, Weeks and Sanborn, David was trying out a gang of NYC kids from the Bronx, whose manager had sent in a demo tape weeks earlier.

They were Carlos Alomar on guitar, his wife Robin Clark on vocals and their vocalist friend Luther Vandross! What a lineup! Mike Garson on piano was the only link left over from the Spiders From Mars days.

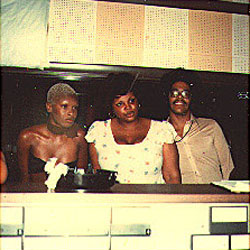

Diane Sumler, Bowie, Robin Clark, Luther Vandross and Ava Cherry

It was agreed we had to record live, no overdubs! But David also wanted to record his vocals live in the same room! This presented a big problem because the instruments were much louder than his voice, so I had to rig up a special microphone technique which canceled the band but recorded his voice. This required two identical microphones placed electronically out of phase. In other words, the diaphragm of one mike is pushing when the other is pulling. The band's sound is picked up by the two mikes, but is out of phase and consequently cancelled! David was told to sing only into the top mike so that his voice was not canceled! For the non-technically-minded this probably doesn't make any sense, but it saved the day, and what you hear on the recordings is about 85% "live" David Bowie.

The sessions went swift as a breeze, and we often worked until after sunrise the next morning (which sometimes hurt). A small group of fans stood vigil outside the studio listening as hard as they could. On the last day David took pity on them and invited them in for an hour of listening.

The ironic thing is that no one was from Philadelphia. Carlos and I are New Yorkers ... Andy Newmark was from California. It was really a fun album but is definitely a hybrid of the sound made popular by The Stylistics, T.S.O.P. and Harold Melvin.

• • •

Philly Stopover: Fans and Funk

Matt Damsker • Rolling Stone • October 1974

PHILADELPHIA - La Bowie and his entourage made elegant camp here for two weeks before the start of the West Coast swing of his current tour. Pitching tents amid the staid and somewhat geriatric prestige of Rittenhouse Square's Hotel Barclay, the Bowie mob had come from its New York headquarters after booking some 120 hours of recording time at Sigma Sound Studios, home of the Gamble-Huff-Bell R&B empire and one of the busiest hitmaking studios in the country.

Bowie's intention had been to record with the rhythm section from MFSB, Sigma's resident body whose TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia) had recently pinned Philly Funk to the top of the charts for an extended reign. However, some confusion over commitments left Bowie with only MFSB conga player Larry Washington.

Bowie then recruited a New York crew: guitarist Carlos Alomar, bassist Willie Weeks, drummer Andy Newmark and saxophonist David Sanborn, in addition to his pianist, Mike Garson, and some rafter-raising gospel in the voices of Ava Cherry, Luther Vandross and Alomar's wife, Robin. Tony Visconti engineered the sessions and was assisted by Sigma's Carl Paruolo.

Accompanied by his secretary, Corinne (Coco) Schwab, and his bodyguard, Stuart George and frequently visited in the studio

by wife Angela and son Zowie, both of whom had checked into the Barclay with him, Bowie made nightly journeys to Sigma.

Carlos Alomar styling Coco Schwab's hair • Stuart George

Mike Garson and Willie Weeks

Robin Clark, Luther Vandross and Ava Cherry

Carlos Alomar and Bowie

Ava Cherry, Robin Clark and Carlos Alomar • Mike Garson

Robin Clark, Ava Cherry, Luther Vandross and Bowie • Carlos Alomar

For a corps of ten "Bowiemaniacs" who maintained

a sleep-out vigil in front of Sigma and who greeted, begged autographs

and won kind words from their main man upon his entrances and exits

(Bowie worked from the early evening into the late morning), the

Sigma sessions were apparently as traumatic as they were God-sent.

Bowie had decided that the faithful would be brought into the studio

after completion of the album for a party.

But that didn't happen until early in the morning

of the final session, after Bowie had put in a long night of finishing

touches some vocal fragments, a few overdubbed keyboard parts and

some additional harmonies from Ava, Robin and Luther.

The album, thanks to Bowie's organized approach he

would prepare reams of precise arrangements during the day for efficient,

methodical run-throughs at night had come together quickly and,

it appeared, to the considerable satisfaction of all concerned.

So much so that, by the final night, the atmosphere in Sigma's second-floor

studio had depressurised to a state of genial calm.

The album, which Mike Garson has suggested Bowie

call Somebody Up There Likes Me, arguably the strongest and most

immediately engaging of the seven songs, seems far from the conceptual

mosaicism of past efforts such as Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs, and is perhaps the first Bowie album you'll be able

to dance to all the way through.

Bowie's version of Philly Sound – a slickly stylised, "discophonic" brand of urban soul pioneered

at Sigma by Kenny Gamble, Leon Huff and Thom Bell – is largely propelled

by the soaring vocal backup of Ava, Luther and Robin, while behind

them the instrumentalists produce a blistering rhythm.

The songs range from a new, remarkably revamped version

of John, I'm Only Dancing – once a straight-ahead rocker and

now rhythmically expanded, ultraprogressive excursion – to new material

in a superbly soulful vein. Apart from the obvious single, Somebody

Up There Likes Me, there is an extended, magnificently punctuated

torch song, It's Gonna Be Me, featuring an aching vocal from Bowie

that should keep Al Green and Marvin Gaye on their toes; bouncy,

high-humoured number, The Young American, written recently enough

to treat Richard Nixon in the past tense, and the album's closer, Right – an exhortation of the funk God.

Bowie with the Sigma Kids • photos by Dagmar

Bowie played the album for the ten blissed-out, formerly

camped-out, devotees, who'd been ushered into the studio, finally,

at 5am by Stuart George. With wine, tears and adulation flowing

around and from the blessed, Bowie was an affable host as he signed

more autographs, apologised for the unfinished mix of the album

and agreed to play it a second time, at which point the party erupted

into dance. Bowie took centre floor with a foxy stomp.

• • •

November 20–24

Sigma Sound, Philadelphia

Footstomping

Can You Hear Me [version 2]

After Today [version 1, slow tempo]

It's Hard To Be A Saint In The City

Bowie's Philly Dogs Tour was bound for Philadelphia so Bowie booked more time at Sigma to rework some of the songs with the tour band. Luther Vandross had been performing his song Funky Music (Is A Part Of Me) as part of The Garson Band's opening set. Bowie took the song and reworked it with new lyrics as the co-written Fascination.

Sunday November 24

Bowie was working on a cover of Bruce Springsteen's It's Hard To Be A Saint In The City which he had started in late 1973, and hoped to get Springsteen involved. Earlier in the week, Tony Visconti called Philadelphia DJ Ed Sciaky at WMMR and asked him if he could get Springsteen into the studio.

Sciaky got in contact with Springsteen who caught a bus from New Jersey to Philadelphia, where Ed and Judy Sciaky found him "hanging with the bums in the station.” At midnight he arrived at Sigma. Mike McGrath was there to document the encounter. Bowie Meets Springsteen

Mike McGrath • The Drummer • November 26,

1974

We arrived at Sigma Sound a little after eight. Producer

Tony Visconti was arched over a mammoth soundboard, pressing buttons,

being generally pleasant to the half-dozen engineers and musicians

in the control room, and peering into the large windowed studio

directly in front.

The album was practically finished. The first rough

mix had been accomplished since Bowie recorded the basic tracks

some weeks ago, and this week had been devoted to clean-ups and

overdubs. This was the final night in the studio for the album -

the final touches would now be made.

I'm Only Dancing (She Turns Me On) was being played

back. Pablo [Rosario] was in the studio, overdubbing a cowbell and some chimes

onto an already lushly produced cut. Visconti easily shows his pleasure

with the final product as Pablo finishes up. The cut is full and

rich, almost a Phil Spector R&B wall of sound - Bowie's voice

mixed way into the background.

Seven minutes to midnight: The door opens and in

saunter Ed and Judy Sciaky, escorting the night's special guest

star, a roadweary Bruce Springsteen, fresh off the bus from Asbury

Park, New Jersey. Bruce is stylishly attired in a stained brown

leather jacket with about seventeen zippers and a pair of hoodlum

jeans. He looked like he just fell out of a bus station, which he

had.

It seems that one of the tracks Bowie laid down was

Bruce's It's Hard To Be A Saint In The City. Tony Visconti called

Ed at WMMR and asked him if he could get Bruce into the studio.

An hour later, the time passing with some more overdubs

and a few improvised vocals by Luther of the Garson band (who sings

a fine lead and whose vocal power adds a lot of strength to an already

powerful album), enter David Bowie and Ava Cherry, white-haired

soul singer for the band.

David breezes in, takes account of the night's progress,

lets his piercing eyes cast across the room a few times, listens

to a tape and then leaves Tony to his work so as to chat with Bruce.

David reminisces on the first time he saw Bruce -

two years ago at Max's Kansas City - and that he was knocked out

by the show and wanted to do one of his songs ever since.

Bowie is a tall skeletal leprechaun. Red beret tipped

extremely to one side, the other revealing a loose patch of orange

hair, leaning away from ears that uncannily resemble a Vulcan's

up close. Intense hawk eyes; if they fix on you friendly it warms

the room; unfriendly or even questioningly you're forced to turn

away from them. Red velvet suspenders over high waisted black pants

and a white pullover sweater complete the bizarre outfit, which,

like any other, grows on you as the hours pass.

After an hour, I couldn't understand how Mike Garson

could say he was easy and friendly to work with; very short and

direct in his instructions to the band as he stands with Visconti

at the board, overseeing some back-up vocals. After a few hours,

a break, and some chatter about flying saucers, the person seeps

through. A real person.

Mike Garson, Bruce Springsteen,Tony Visconti, Carl Paruolo, Bowie

The studio is a warm, fur covered cavern at 3am.

Heads and bodies sway in time to a slow one. Yellows, blues, reds,

and greens dimmed as low as possible light the control room and

studio.

Bowie tried to record a vocal solo. It sounds terrible,

the voice is hoarse and tired. "It's much too early yet - I'm not

quite awake… I won't be able to record anything till about half

past five."

He re-enters the studio and wraps a set of incredibly

long, slender fingers around a cold steak sandwich (never having

encountered one before, he was taught the correct hold and given

seven different explanations as to what a hoagie was).

After a promise to meet again and talk further in

New York, Bruce heads off with Ed and Judy for a 5am visit to the

Broad Street diner. Max's Kansas City had been his first professional

gig. Bowie was in from the start. Bruce leaves without having heard

his version of Saint. The feeling is that it's not ready yet.

Outside, a dozen sentinels are huddled in cars, standing

on the sidewalk, sitting on the steps, waiting for a little of the

magic to pour out. This is Bowie's final night in the studio. When

he leaves, they'll get into their cars and beat him to the Barclay.

One last look at the man who makes his albums in Philadelphia.

December 1974

Record Plant, New York

Win

Fascination

Tony Visconti: We didn't have enough songs recorded, so David wrote Win, and turned one of Luther Vandross' songs – Funky Music – into Fascination by changing the title and some of the lyrics. David Sanborn added some more sax to these and some of the Philly tracks. The day arrived that I was ready to take the tapes back to London to mix the album, tentatively called The Gouster.

On my last night in New York, David phones my hotel room and says that John Lennon is coming that evening and he's a little nervous to be left alone with him, could I come? I was over there in a flash! After ringing the doorbell many times I was finally let in. It seems that Lennon was a little nervous because he didn't have his alien's green card yet, and thought that I might be the police. Out of the bathroom walks John and his Chinese-American girlfriend, May Pang (who became my wife 13 years later).

David sits on the floor and avoids eye contact with John, sketching on a notepad instead. I take this as a cue to begin to ask John Lennon at least 100 questions I always wanted to ask a Beatle, like, "What is that guitar chord at the beginning of A Hard Day's Night?" He told me and we chatted away for hours.

May and Beatles exec Neil Aspinall sat quietly for that time, as did singer Ava Cherry. David continued to sketch. Finally John said, "Let's see what you're drawing." They were portraits of John. John sat on the floor, picked up another pad and began sketching David. They finally broke the ice.

January 1975

Electric Lady, New York

Across The Universe

Fame

In 1983 Bowie told Timothy White (Musician magazine) how the Fame recording session with John Lennon came about.

Bowie (1983): We'd spent quite a few nights talking and getting to know each other before we'd even gotten into the studio. That period in my life is none too clear, a lot of it is really blurry, but we spent endless hours talking about fame, and what it's like not having a life of your own any more. How much you want to be known before you are; and then when you are, how much you want the reverse: "I don't want to do these interviews! I don't want to have these photographs taken!" We wondered how that slow change takes place, and why it isn't everything it should have been.

I guess it was inevitable that the subject matter of the song would be about the subject matter of those conversations. God, that session was fast. That was an evening's work! While John and Carlos Alomar were sketching out the guitar stuff in the studio, I was starting to work out the lyric in the control room. I was so excited about John, and he loved working with my band because they were playing old soul tracks and Stax things. John was so up, had so much energy; it must have been so exciting to always be around him.

Having recorded Across The Universe and Fame, Bowie decided to include them on the new album, replacing Who Can I Be Now and It's Gonna Be Me – much to Tony Visconti's dismay.

Tony Visconti: A week or so later I was in London mixing the album and I got a call from David. "Er, Tony. I don't know how to tell you this but John and I wrote a song together and we recorded and mixed it. It's called Fame."

He explained that he went back to the studio and recorded Lennon's Across The Universe for a lark and it turned out good enough to include on Young Americans. He later played the track to Lennon, who thought it was cool, then David asked him it he would like to write and record a new song together. This led to the making of Fame. David apologised for not including me. There wasn't time left to send for me, because of the release date constraints.

For me, it would've been the most wonderful experience of my recording career. Oh well. This is, nevertheless, definitely one of my favourite Bowie albums. As I walk through gallerias the world over, I hear the title track wafting out of boutiques to this day. [Tony Visconti's website]

John Lennon (1975): David told me he was going to do a version of Across The Universe and I thought 'great' because I'd never done a good version of that song myself. It's one of my favourite songs, but I didn't like my version of it. So I went down and played rhythm on the track. [Charlesworth, Chris. Rock on! (Melody Maker, 8 March 1975)]

Having finished the song, Lennon suggested they do something else. Bowie suggested they try Footstomping, a 1961 Flares song he’d played during November shows including The Dick Cavett Show. With a new riff from Carlos Alomar, the song evolved into Fame.

Bowie (1983): We'd spent quite a few nights talking and getting to know each other before we'd even gotten into the studio… we spent endless hours talking about fame, and what it's like not having a life of your own any more. I guess it was inevitable that the subject matter of the song would be about the subject matter of those conversations. God, that session was fast. While John and Carlos Alomar were sketching out the guitar stuff in the studio, I was starting to work out the lyric in the control room. [White, Timothy. 'The Interview’ (Musician, May 1983)]

John Lennon (1980): He goes in with about four words and a few guys, and starts laying down all this stuff and he has virtually nothing – he’s making it up in the studio. So I just contributed whatever – you know like backwards piano and oooohhh [hits a high note] and the repeat of Fame. Then we needed a middle eight so we took some Stevie Wonder middle eight and did it backwards, you know. And we made a record out of it, right? So he got his first number one so I felt that was like a karmic thing, you know. With me and Elton, I got my first number one so I passed it on to Bowie and he got his, and I like that track. [Peebles, Andy. The Lennon Tapes - John Lennon And Yoko Ono In Conversation With Andy Peebles, 6 December 1980 (BBC, 1981)]

Bowie (1976): There's always a lot of adrenalin flowing when John is around, but his chief addition to it all was the high-pitched singing of Fame. The riff came from Carlos and the melody and most of the lyrics came from me. But it wouldn't have happened if John hadn't been there. He was the energy, and that's why he got a credit for writing it. He was the inspiration. [Charlesworth, Chris. Ringing the changes (Melody Maker, 13 March 1976)]

Unaware of the new recordings, Visconti had couriered a copy of the finished mixes of the album to Bowie.

Tony Visconti (1985): About two weeks after I’d mixed the album, David phoned me to tell me about Fame. He was very apologetic and nice about it, he said he hoped I wouldn’t mind if we took a few tracks off and included these. I first I heard of Fame and Across the Universe was when the record was released! [Thompson, Dave. Moonage Daydream (Plexus, 1987)]

Bowie decided the two new tracks would replace Who Can I Be Now and It's Gonna Be Me.

Tony Visconti (1985): Beautiful songs, and it made me sick when he decided not to use them. I think it was the personal content of the songs that he was a bit reluctant to release. [Thompson, Dave. Moonage Daydream (Plexus, 1987)]

In 1991 the tracks were released on Ryko's reissue of Young Americans.

Further reading

Heart and Soul by John Robinson (Uncut, February 2015) |