1970 • 1971 • 1972 • 1973 • 1974

1975 • 1976 • 1977 • 1978 • 1979 • 1980

THE MAN WHO SOLD THE WORLD • HUNKY DORY

THE RISE AND FALL OF ZIGGY STARDUST

AND THE SPIDERS FROM MARS

ALADDIN SANE • PINUPS • DIAMOND DOGS

YOUNG AMERICANS • STATION TO STATION

LOW • HEROES • LODGER • SCARY MONSTERS

ZIGGY STARDUST THE MOTION PICTURE

THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH • THE ELEPHANT MAN

FEATURES • PRESS ARCHIVE

BOWIEGOLDENYEARS is currently being expanded and redesigned

gold page links are live

|

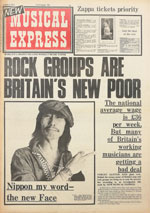

Bowie-ing out at the Chateau Charles Shaar Murray • New Musical Express • 4 August 1973

Charles Shaar Murray with the main man in France. Work on new projects, reports Murray, is going ahead deliciously in the dead of night. "The future is very open-ended, actually," said David Bowie, carefully disassociating a quarter of an inch of ash from his Gitane. "I can't tell you much about what I'm doing because I'm not really too sure yet. There's not much to add to what you already know." Bowie is perched on a chair behind the control board of the studio in the Chateau d'Herouville, about to start another day's work on his Pinups album. He's slightly less than immaculate: slightly stubbled, hair in disarray, face drawn and even whiter than usual, wearing a scoop-necked blue tricot and cream coloured Oxford bags. Working togs in fact. Superstars finery is generally unsuited to the private labours of painstakingly assembling a rock n roll record, and the rustic elegance of the Chateau blends uneasily with such fripperies. After all, it's buried in the French countryside half an hour out of Paris, and it's the sort of place where you find a couple of dead daddy longlegses in your toothpaste. Work continues apace. Mick Ronson, the guitarist who launched a thousand fan letters and a similar number of plaudits from knowledgeable folks in several countries, is never seen without felt-tip pen and sheets of manuscript paper. Even at breakfast, Ronson is working on string arrangements or dreaming up vocal harmony lines. Unlike some members of our merry cast, Ronno has not spent several hours of each night carousing in the bistros and discos of the City Of Light. In fact, he hasn't been out of the Chateau grounds in three weeks. Mike Garson and Trevor Bolder are long back in England, but Bowie and Ronson are putting in absurd amounts of studio time with Ken Scott, co-producer supreme. Aynsley Dunbar has completed all his percussion tracks, but he's still around, wearing a magnificently studded and rhinestoned denim jacket with his name emblazoned on the back, and so many rings and bracelets that he clanks when you shake hands with him. Today is Vocals Day. The instrumental tracks for the album are all but completed, barring a guitar here and some strings and a Moog there, and so it's time for Bowie to put the lead vocals on. Apart from a meal break, he, Ronson and Scott are up in the studio well over 12 hours. Pinups is Bowie's tribute to the club rock of the 60s, and the items on the agenda include such classics of yesteryear as Here Comes The Night, See Emily Play and Shapes Of Things. He stands in the studio, hands clasped to his earphone, stopping the take if he's dissatisfied with his intonation or phrasing. Between takes, he prowls over to the piano and plays over his part before going for another try, bending the melody line in a slightly different direction each time, curtly snapping instructions over the studio intercom. On See Emily Play, Bowie embellishes the Floyd's old hit with a vocal device that would have Syd Barrett gurgling in sheer ecstasy. He and Ronson record their vocal harmonies over and over again at different speeds, with the same harrowing culminative technique produced at the climax of The Bewlay Brothers. Some of the songs are performed in the style of the mid-60s, like the semi-legendary Pretty Things tune Rosalyn with its coarse high-energy vocal and rubbery Bo Diddley guitar. Others get – uh – revamped. Billy Boy Arnold's I Wish You Would, which had the signal honour of appearing on the first ever Yardbirds single, gets sprucely turned out with some eerie moog work and a manic, squealing fiddle solo from a moustachioed gent called Michel, who works in a French band called Zoo. "Can you bring the bass drum up a bit, Ken?" asks Dunbar. Scott mimes surprise. "All right, Aynsley," he says; "You don't have to prove that you're here." Dunbar repeats his request. "So that's what's keeping the beat." "It certainly ain't the piano," retorts the drummer. At the other end of the studio, Bowie and Ronson are rehearsing yet another harmony. They go in to record it, Ronson balancing a singularly improbable white hat on top of his cans. The backing track kicks off, and as Ronson leans into the mike to start singing, the hat falls off. With perfect coordination, he scoops it up and still comes in on time. Unfortunately, Bowie has collapsed laughing and it's a good five minutes before he's in a fit state to sing again. Meanwhile, social life continues apace. The Chateau is blessed with a lame excuse for a telephone switchboard that reduces Bowie's assistant Gloria to impotent fury, and a chef of dubious eccentricity. One of his favourite tricks is to dress up as Charlie Chaplin and provide before-dinner entertainment. For after-dinner entertainment there's a football machine, heavily patronised by Ken Scott, engineer Andy, equipment man Pete and Aynsley Dunbar. During-dinner entertainment generally involves badinage of varying intensity, and the two favourite butts for the humour are Stuey the bodyguard and the unfortunate Ronson, still working away with the manuscript paper. Apart from Pinups, there are also the tapes of that last Hammersmith gig to work on. Without exception, each live track cuts its studio original completely dead, and the guest appearance of Jeff Beck on Jean Genie and Around And Around was definitely an inspiration. When the famous retirement speech comes up on the speakers, Bowie grimaces slightly. To say that his face shows mixed emotions is definitely an understatement. |

|

Bowie Golden Years v1.0 created and designed by Roger Griffin 2000

Bowie Golden Years v2.0 2017-2020

Photographs and texts have been credited wherever possible

this page updated February 11, 2022